Energy, enthusiasm, and an entrepreneurial spirit are great assets to possess when launching a business venture. They often are not nearly enough.

According to BLS data, about 20% of businesses with employees fail within the first year, regardless of the industry or the state of the economy. There are many reasons why small businesses fail including poor financial planning and lack of market demand.

If you are going it alone as a sole proprietor, survival can be even more challenging because you are responsible for literally every aspect of your business.

The question is:

How can you stop your small business from failing?

Well, you should first start by understanding why small businesses fail and then take measures to ensure that your business doesn’t meet that fate. In this post, we’ve covered both in detail. Let’s get started.

Why Do Small Businesses Fail in the First Year

There are myriad reasons for these first-year failures, but some issues consistently stymie startups more often than others. Here are some of the top downfalls that prompt businesses to cease operations within the first year.

1. Cashflow Problems

One of the biggest reasons why small businesses fail is insufficient funds for running day-to-day operations.

A lack of capital or adequate financing from external channels signals trouble. Spending money faster than you’re taking it in — even if it’s to stock up on inventory — can be equally detrimental.

It is important for small businesses to have enough working capital to run daily operations, pay employee salaries, and take care of fixed and variable expenses. That’s why you need to be aware of your revenue and expenses to strike the right balance.

Here are some common reasons why new businesses face cashflow problems:

- Failure to understand the cost of running a business

- Setting lower prices than what’s required to bear the costs

- Inability to secure external funding

- Poor inventory management and stocking more than you can sell

- And myriad other reasons related to poor planning and management

The reason why small businesses fail due to money problems is poor planning. Many startups secure funding to start the business but don’t consider the operational costs and soon run out of money.

You can avoid these problems by properly planning your finances and correctly estimating your operational costs. Understanding how much money you’ll to run your business will help you plan better before you even launch your business.

2. Lack of Market Demand

One of the common reasons why small businesses fail is a lack of market demand for their products or services.

Many products or services simply are not needed or wanted, no matter how much an entrepreneur may treasure them. If people don’t need or want your products or services, they will not sell and your business will fail. Even if you use the best marketing tactics to generate demand, it can’t guarantee success.

That’s why you need to do proper market research to see if there’s a demand for your products before you start your business. Test your business idea and see if it’s feasible and if there’s a market need for it. If not, move to your next idea.

You should also conduct detailed competitive research to understand the level of competition in the market. Identify the key players, their offerings, and their prices.

Competition and pricing are key factors that can chip away at demand for your offerings. If you’re offering something that already exists in the market at better prices, it’s not likely to sell.

If you want to create demand for your offerings, you need to either provide something different, more valuable, or cheaper.

3. No Business Plan

Whatever your product or service, the market will have a lot of moving parts. In the absence of strategies for handling financial challenges, staffing changes and possibly having to adjust your role, you’ll be making important decisions with no forethought.

Having a well-defined business plan helps you think ahead and anticipate possible challenges that may arise along the way. It can help you plan better and be prepared for starting and running a business while avoiding common pitfalls.

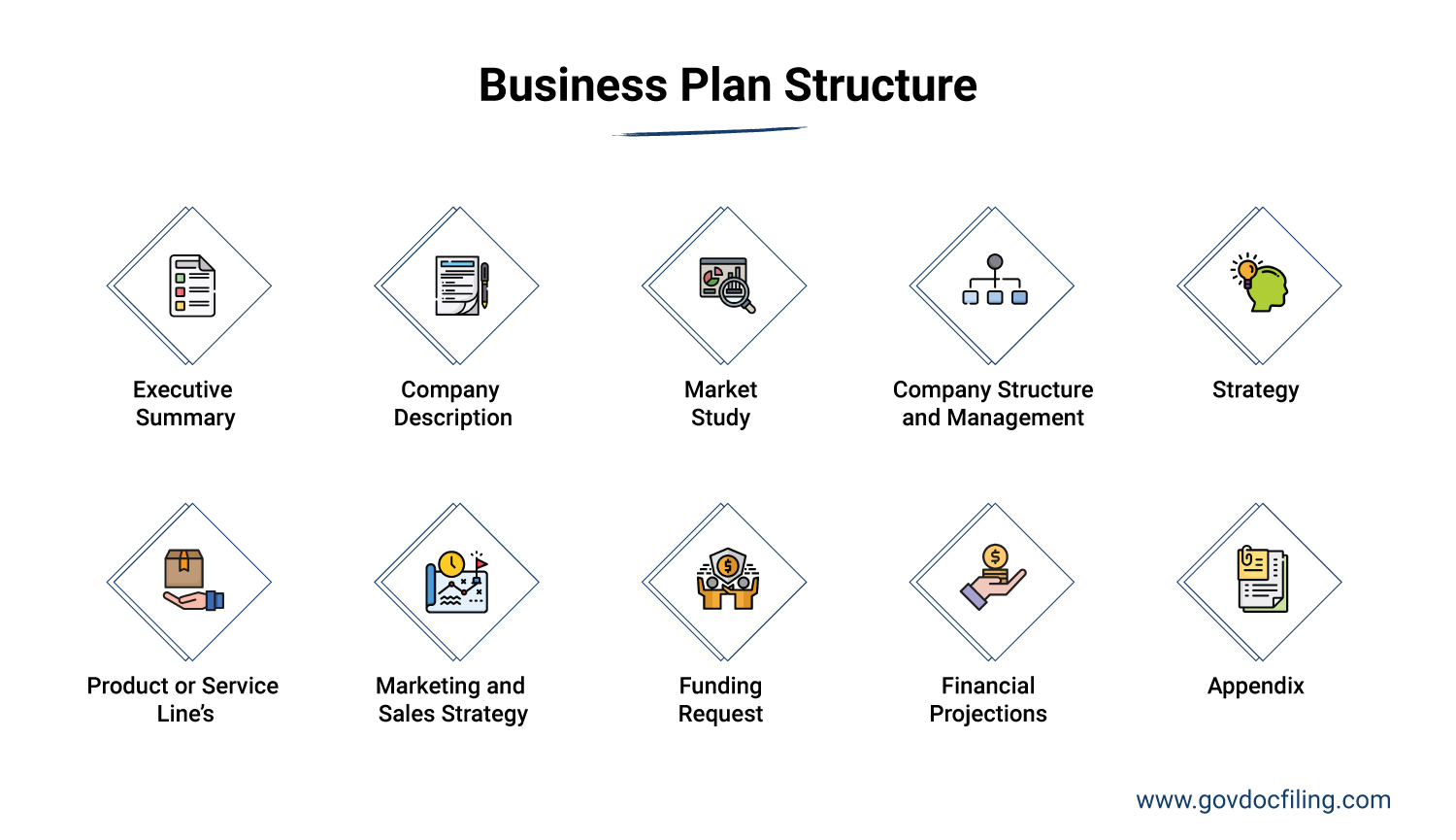

That’s why you need to prepare a business plan before you launch your business. Make sure that it includes:

- A clear and concise description of your business

- Business goals, vision, and mission statement

- Details on your products and services and why they’re needed

- Market analysis, along with a list of potential threats

- Competitor analysis with a list of key competitors and their offerings

- Capital requirements for starting and running your business

- Financial projections and revenue estimates and the plan for breaking even

Here is a visual representation of the key elements of a business plan:

4. Poor Location

Choosing the wrong location for a business is one of the reasons why small businesses fail. A great product offered in the wrong place at the wrong time isn’t so great after all.

Why does location matter?

Consider these scenarios to understand that:

- You open a retail store in a secluded area and get very less footfall solely because of the location of your store.

- Your office or warehouse is located at a prime location where the rent is extremely high, which causes unnecessary costs that could have been avoided.

- The business you start has a niche target market and you open your business in an area where your target customers are not present. Your business will fail.

There could be numerous such scenarios where your business location could affect your chances of success. You could have a great business idea and amazing products but if you choose the wrong location, your business may still fail.

That’s why it’s important to choose the right location considering some important factors. Choose a location that:

- Has your target customers

- Is affordable in terms of rent or real estate costs

- Is convenient in terms of day-to-day operations

- Does not have too many competitors vying for the same target customers

- Provides easy access to and parking for your customers

- Meets other important criteria specific to your industry or type of business

The idea is to choose a location that is cost-effective and convenient from a business point of view and easy for your target customers to access.

5. Inadequate Management

Mistakes happen—the real trouble comes when problem-solving skills are lacking due to inexperience, hiring the wrong team, etc.

Any new business faces challenges and unexpected situations, no matter how much you plan ahead. A strong management team can think on its feet and overcome these challenges head-on, while weak management may make mistakes that can lead small businesses to fail.

Sometimes small businesses may not even have a managerial team and might rely on the business owners to take on multiple roles. While that may be out of necessity, we recommend onboarding at least one senior manager as soon as possible.

This will ensure your business runs smoothly, despite unexpected hurdles arising from time to time.

Lax oversight of employees is another typical factor in failure. A strong management team can help you overcome that as well.

6. Marketing Mishaps

Reaching your potential requires reaching customers — and keeping them engaged over the long haul. One way that businesses invite failure is by foregoing having a website, even in these digitally dominated days.

A website acts like the single source of truth for anyone looking to find more information about your business. It helps your prospective customers understand what you offer and what makes you stand out.

Not to mention that a website is one of the best ways to generate leads and drive conversions. If you optimize your website for the right keywords you’ll generate organic traffic, which could turn into potential customers.

Another big marketing mistake that new businesses make is not having a social media presence. Any brand that wants to reach new customers and engage existing ones meaningfully, should use social media. It provides a unique opportunity to connect with your target audience where they’re most active.

A few more reasons why small businesses fail due to marketing mistakes are overspending or underspending on marketing, using the wrong marketing channels, and thinking of marketing as a one-time thing, not an ongoing activity.

7. Poor Customer Service

One of the biggest reasons why small businesses fail is poor customer service. You can do everything right and still fail if you don’t treat your customers right.

In this day and age, customer service tops everything. Customers prefer brands that make them feel special and go above and beyond what’s expected to deliver personalized customer experiences.

Customer expectations have also skyrocketed. It’s not enough to just deliver high-quality products, you need to do it in a way that delights customers.

How can you deliver exceptional customer service in such a demanding landscape?

Start by providing customers with multiple options to connect with your business. Provide seamless omnichannel support via phone call, email, and chat. Also, quickly respond to customer comments and messages on social media.

A quick and hassle-free experience with your customer support team will win customers over, even those who had a complaint or a bad experience.

8. Unsustainable Growth

One of the lesser-known reasons small businesses fail is expanding too quickly or growing at a pace that is unsustainable.

It might seem counterintuitive. After all, why should business growth be a reason for failure, right?

Well, it can be a problem if you don’t have the capability and resources to meet the unexpected rise in demand.

That’s why it is prudent to expand your business slowly and steadily, instead of doing it all at once. Whether it is geographic expansion or entering new product categories, you should make sure that you’re ready to take on the new challenges associated with business expansion.

If you try to bite more than you can chew your quality is bound to decline, which would cause customer dissatisfaction and damage to your reputation.

Once you have established a loyal customer base and a steady revenue stream you can think about growing your business at a realistic pace. Before every expansion plan, do your research to understand the market and then take steps to expand in a planned manner.

Here are some signs that tell if there is a need for business expansion:

- There’s more customer demand than you can meet. This calls for an expansion of your production facilities.

- Your industry or niche is growing rapidly and there is scope for capturing a much larger market.

- You have excess funds that can be used for business expansion.

- There is an opportunity for you to enter an underserved niche that is related to your current business.

- Your customers are looking for new products or features and you have the capability to meet that demand.

9. Not Adapting to Changes

One of the lesser-known reasons why small businesses fail is the inflexibility in adapting to changes.

The business environment and consumer needs are everchanging and evolving. Fax machines were extremely popular one day and rendered useless the next with the advent of email and other digital technologies. Blackberry phones were at the top of their game and were replaced by smartphones overnight.

Needs change, technology advances, and businesses become obsolete.

In a dynamic business environment, the best way to continue being successful is adapting to changes quickly. Be ready to pivot your business in a different direction, if things are not working out anymore.

The biggest example in recent history is the global COVID-19 pandemic that caused many small businesses to fail. Only those that adopted new ways to run their businesses survived.

That’s why it’s important to not be too attached to the current way of doing things and be more flexible. This is one of the most important factors that will determine your business’s success or failure.

How to Avoid Failure

The good news is that there are about 30 million small businesses operating in the U.S., which means many survive their first year and well beyond that. So instead of asking, “Why do most businesses fail in the first year?”, why not ask, “What can be done to stay in business?”

Let’s discuss some important factors that can help you avoid this fate and make your business a success.

1. Study the Market and Make a Plan

Conducting a market study will help determine the demand for your product or service, as well as strategic locations. Entities such as the U.S. Small Business Administration can help you create a business plan.

Here are some questions you should be able to answer through your market research:

are some questions you should be able to answer through your market research:

- Is there a real demand for your products or services?

- What is the estimated market size for your business?

- Who are your target customers?

- Who are your competitors and what is their strategy and positioning?

- What can you offer that your competitors don’t?

- How can you position your brand to capture the market?

- Where will you open your business and what strategic advantages does that location provide?

- How will you price your products?

- How much do you anticipate your revenue and operating expenses to be?

- When do you expect to break even and what’s your plan for that?

Do your research and answer these questions to check if your business is even feasible. If it passes the feasibility test, plan for how your will start and run your business to avoid failure.

2. Plan Your Finances

As mentioned above, one of the main reasons why small businesses fail is poor financial management. That’s why you need to be thorough when planning your business finances if you don’t want to fail.

Start with a cash management plan. Don’t use all of your startup capital before your business is cash flow positive.

Ensure that you have enough working capital to not only run your day-to-day operations but also handle any unexpected costs. Keep a contingency reserve for emergencies.

Here are some tips to maintain a positive cash flow:

- Bill your customers and collect payments quickly if you’re running a B2B business. Avoid long payment periods or monthly invoicing. Instead, send invoices as soon as an order is delivered.

- Don’t spend all your cash on overstocking inventory and maintain a lean inventory management system.

- Liquidate assets that are not in use like old equipment or excess inventory.

- While you must collect receivables quickly, you should also delay your payables to have more cash in hand at any given time.

You should also open a separate bank account for your business. Our trusted banking partner Chase Banking provides some excellent business banking options that you can check out.

Also, don’t forget to insure your business to recover from unexpected circumstances. Here are some common types of insurance covers businesses need.

You can use the services of our trusted partner Hiscox Insurance to insure your business.

3. Choose the Right Business Structure

One of the most crucial business decisions small business owners make is choosing the right business structure or entity for their business. This will play a role in your ability to get a small business loan, how easily you may be able to have investors, your tax liability and more.

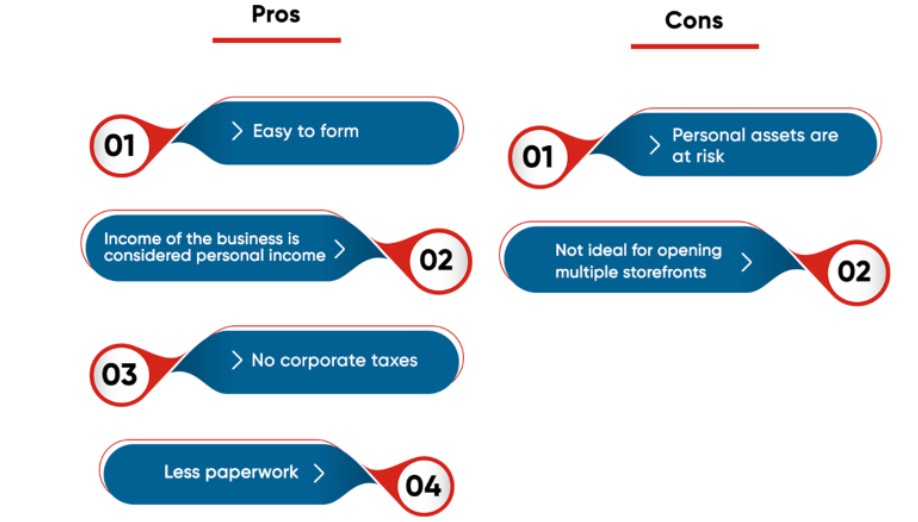

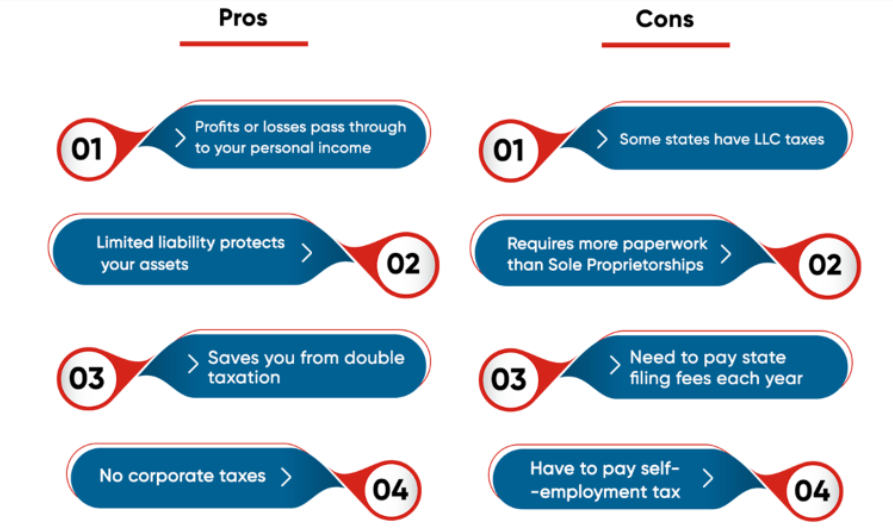

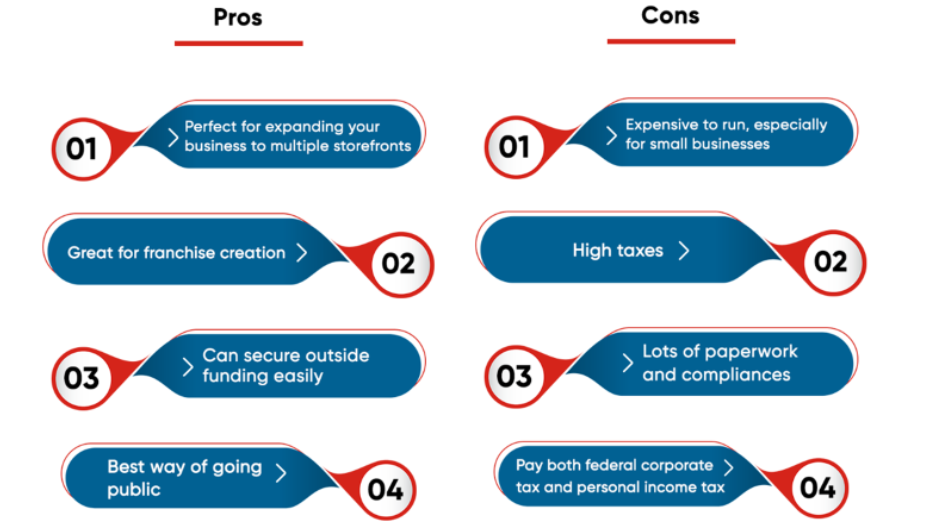

Sole proprietorships, LLCs, and corporations are all great options, but you must understand their pros and cons before you choose an entity.

Here is a quick guide to help you make the right choice:

- Sole Proprietorship: This is the perfect choice for local, small businesses that are family-owned. It provides you complete control over your business, has low startup costs, and is easy to run. The main problem, though, is that the business owner is solely responsible for all business profits and losses.

- Partnership: This entity is preferred by licensed professionals who want to run a business with one or more partners. It’s perfect for starting a consulting business or a law firm. Partners share profits and losses in a predetermined proportion. There is no liability protection, just like sole proprietorships.

- Limited Liability Company: This is the most popular business structure for small businesses as it offers the best of both worlds. You get the pass-through taxation of sole proprietorships and partnerships and the liability protection of corporations. That’s why forming an LLC is perfect for small businesses that want to protect their personal assets if their business fails.

- Corporation: This is the best option for mid-sized and large businesses that want to operate in multiple states or countries. If you form a corporation, you can issue shares and go public to raise funding and expand your business. Just like an LLC, a corporation is also a legal entity separate from its owners, so owners’ personal assets are protected from business debts and liabilities.

Irrespective of which entity you choose, GovDocFiling can help you register your business and take care of all the paperwork while you focus on business growth. Choose our business formation packages to start your business on the right foot.

4. Build a Strong Team

If your business will have employees, take your time and hire wisely, collecting as much background information as possible on prospective employees.

As a small business, you would probably start by hiring the most essential employees that are crucial to your core business. You must, however, bring in a good management team as early as possible.

As mentioned earlier, strong management can often be the difference between success and failure. A management team will not only oversee the work that your employees do, but will be useful for making crucial business decisions and overcoming any potential challenges.

5. Make a Solid Marketing Plan

When starting a business, you should have a pre-launch and post-launch marketing plan for your business.

Don’t wait for your business to start operations before you start marketing it. Instead, start with a pre-launch marketing plan to create buzz around your new business and spread awareness among your target market.

You can start by creating an SEO-friendly website and providing information on what products and services you will offer. Also, market your upcoming business on social media and get people excited about your business launch.

Once you start your business, you can use word-of-mouth marketing and advertising to generate leads and attract customers. Social media marketing will again play a crucial role in spreading the word about your business and promoting your products and services.

6. Continually Learn and Grow

One of the reasons why small businesses fail is that they don’t learn from their mistakes and change their course of action.

When you start a new business, you are bound to make mistakes and face unexpected challenges. If you don’t want your business to fail, you should learn from your mistakes and improve your strategy along the way.

This will help you avoid repeating mistakes and do better and better as your business grows. It might seem like a simple thing, but it’s the most important factor that determines a business’s success or failure.

Be flexible, be adaptable, and learn from your mistakes to run a successful business.

FAQ

1. What are the common reasons why small businesses fail?

Here are the top reasons why small businesses fail:

- Cashflow Problems: Lack of financial planning and poor cash management often cause new businesses to run out of money and close down.

- Lack of Market Demand: Many small businesses fail because they do not conduct market research and offer products or services that have no demand.

- No Business Plan: Lack of planning can cause companies to face challenges that they’re not prepared to handle.

- Poor Location: Sometimes the right business in the wrong location can fail because it’s not easy for customers to access or not cost-effective for the business.

- Inadequate Management: Weak management is one of the main reasons why small businesses fail.

- Marketing Mishaps: Lack of a website and social media presence can be detrimental to a business’s success.

- Poor Customer Service: A company that does not treat its customers well will never succeed.

- Not Adapting to Changes: Being rigid and inflexible is a sure way of becoming obsolete in a dynamic business environment.

2. What is the failure rate for small businesses?

According to BLS, almost 20% of businesses fail within the first year. This rate varies from industry to industry and can be higher for some industries.

3. What is the #1 reason small businesses fail?

Lack of planning, whether it is in terms of managing finances or marketing, is the top reason why small businesses fail.

That’s why it’s important to conduct market research and make a business plan before your start a new business. Proper planning can prepare you for the challenges of running a new business and give you the right tools to succeed in your business venture.

4. What are the biggest risks for small businesses?

Here are some of the most common types of business risks that may cause small businesses to fail:

- Financial Risks: The biggest risk that small businesses face, which is also one of the top reasons why small businesses fail, is financial risk. Poor financial planning or cashflow management could cause a company to run out of money.

- Compliance Risks: All business need to comply with laws and regulations of the state they’re operating in and failure to do so could cause penalties and remove a business from good standing with the government.

- Strategic Risks: A poor business strategy or a failure to execute the strategy well could cause business failure. Strategic risks arise from the decisions taken by senior management and owners of a company that turn out to be huge mistakes.

- Operational Risks: These risks arise from operation issues like equipment failure or human error. Anything that can break down or disrupt the day-to-day business operations is an operational risk for a business.

- External Risks: These include economic, environmental, political, and social factors that can affect a businesse’s performance or are a threat to its survival

5. How can new businesses avoid failure?

Here are some important tips to help new businesses avoid failure:

- Study the market and make a plan

- Plan your finances

- Choose the right business structure

- Build a strong team

- Make a solid marketing plan

- Continually learn and grow

Get Started With GovDocFiling

There are many reasons why small businesses fail and small businesses with small startup capital are even more at risk. That’s why it’s prudent to understand the reasons your business may fail and take measures to avoid any pitfalls.

For entrepreneurs preparing to start a business, GovDocFiling is here to help. We provide the critical tools needed to build a strong foundation. Get started today with our EIN filing forms and take advantage of our many other business formation services.

About the author

From selling flowers door-to-door at hair salons when he was 16 to starting his own auto detailing business, Brett Shapiro has had an entrepreneurial spirit since he was young. After earning a Bachelor of Arts degree in Global and International Studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and years traveling the world planning and executing cause marketing events, Brett decided to test out his entrepreneurial chops with his own medical supply distribution company.

During the formation of this business, Brett made a handful of simple, avoidable mistakes due to lack of experience and guidance. It was then that Brett realized there was a real, consistent need for a company to support businesses as they start, build and grow. He set his sights on creating Easy Doc Filing — an honest, transparent and simple resource center that takes care of the mundane, yet critical, formation documentation. Brett continues to lead Easy Doc Filing in developing services and partnerships that support and encourage entrepreneurship across all industries.